Navigating Grief in the Workplace

The worst reaction to grief, is no interaction at all

For a process that is widely accepted as ‘a part of life’, dealing with grief could not come more unnaturally to us.

It’s abrupt. It’s unprecedented. And it’s always underprepared for.

I feel the way grief is often socially outcasted comes from our instinct to keep it away. It’s never invited anywhere, and understandably so. There’s an instinct to protect ourselves from something so painful and sad.

Whilst we no longer receive daily notifications of death tolls from the pandemic, we might assume that topics like grief have grown some substantial social footing in our day to day, where the likelihood of knowing someone connected to grief seems more likely than ever before. But the taboo still creeps in, along with the panic of not knowing what to say or do.

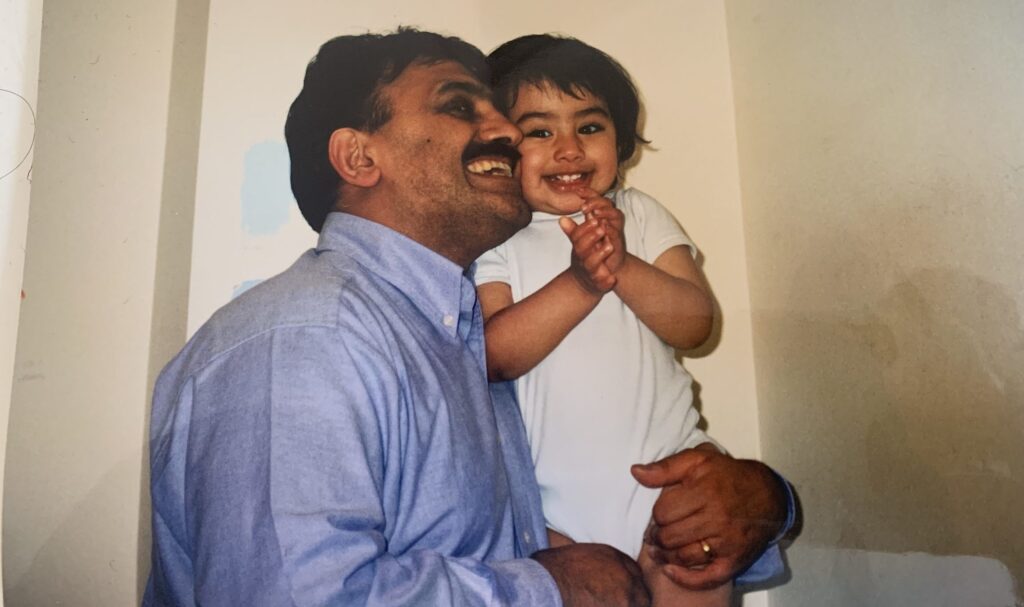

My grieving process began when I was 19 years old in June 2020, after losing my dad and it could not have been more unprecedented.

Without warning, a blanket of grief smothers your life and before you even realise, your life and who you are permanently change. The panic of not knowing what to do followed me around for the best part of a year. And I’ve found one of the biggest challenges is introducing and incorporating it into all the many facets and environments of my life, each one having it’s unique conditions and expectations.

You ask yourself questions like, ‘Is this a safe space?’, ‘what’s appropriate to express’, and even ‘where’s the closest bathroom or hiding nook in case I have a moment?’. The workplace is no different.

It comes with it’s own conditions and holds the potential of discomfort due to an expectation of professionalism – something grief clashes with. Most of us are still aware of and expect work cultures of the past where you’d leave personal plight at the door. But in a world of work that is becoming increasingly concerned with wellbeing, mental health and empathy, leaving it all at the door isn’t as common or feasible.

And the idea of ever being able to ‘leave’ something like grief ‘at the door’ is unimaginable, once you experience its weight. So, as an employer, what’s best practice for dealing with grief in the workplace?

Short answer: there’s not an exact formula, but it doesn’t need to be a minefield.

Here are a few helpful suggestions that can help to guide grief related situations that create open dialogues and safe environments.

Transparency

In a situation where things might be as bad as they can get, clarity can provide great relief. Whether it’s with the employee experiencing it or those they work alongside, being transparent with communication is key. This might be in the way of:

- Understanding the realities of the situation allows employees and colleagues to make the most informed and sensitive decisions they can.

- Perhaps your company has financial or wellbeing policies. Making these clear to employees and significant external others, such as family members of an employee who might have passed away, acts as a practical comfort.

- Be it emotional or practical, communication needs to be as transparent as possible. This might seem obvious, but in times of intensity, we can lose our basic communication styles to our personal responses.

- For individuals and the workforce, making it clear to people what and who is available to help.

Reach out

We can’t possibly help every individual through grief with the same approach each time. Instead, reaching out as much as we can, be it counselling support or an open-door policy, lays the foundation for open dialogues. Especially from the perspective of a manager, firstly focusing on reaching out to employees, rather than tailored grief support for everyone, helps to manage the initial impact of grief in the workplace.

It’s about pushing through that awkwardness to reach out with compassion.

Organic Process

There is no path well-trodden with grief. Appreciating the process as free form and organic, rather than through the classic tick box stages (anger, denial etc.) allows employees to breathe and grow with their grief.

When we reach out organically to individuals, instead of rushing people to fit within a process with a deadline, we show compassion, prioritising our people. We allow people to breathe outside of the organisation, marching to their own drum of grief.

Human Response

Grief feels surreal and inhumane. The best way we can make the workplace a more hospitable environment for grief is to humanise it as much as we can, normalising it with the same approachability as we do with other personal issues.

- How do we normally approach people when they’re upset?

- What’s our normal response when we notice someone isn’t being themselves?

We can re-centre ourselves when we feel out of depth with grief by remembering what our normal instincts would be in any other given situation. Even just offering someone a chat is sometimes all a person needs. By creating an opportunity for people to speak, we validate that their voice and feelings matter – something that grief can make even the most confident person doubt.

‘[people] share a need for their grief to be witnessed. That doesn’t mean needing someone to try to lessen it or reframe it for them. The need is for someone to be fully present to the magnitude of their loss, without trying to point out the silver lining.’

David Kessler (Unlocking Us Podcast, Ep. 5 with Brené Brown)

From all my interactions with grief – my own and others, for my father or their loved one, the truest sentiment is that:

The worst reaction to grief, is no interaction at all.

As David Kessler explains, those who grieve are never looking for an explanation. And as those supporting, whether you’re a colleague or manager, our job is never to provide one. The best thing we can do is to produce as much compassion as we can for that person, whilst they meet and learn to live with the new version of themselves.